Discuss the Quest for Racial Equality and Its Proponents in the Arts

O due north fourteen May 1857, 39-year-old abolitionist Frederick Douglass delivered an impassioned voice communication to a oversupply that packed a Prince Street church in lower Manhattan for a meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Two months earlier, the supreme court had ruled in a landmark case confronting Dred Scott – a Missouri slave who sued for his freedom – deciding that no black person, gratuitous or enslaved, could ever be a US denizen. In his speech, Douglass sought to beacon the crowd's resolve, urging them to take the long view and arguing that the national backlash to the Scott example could ultimately assistance advance their quest for equality.

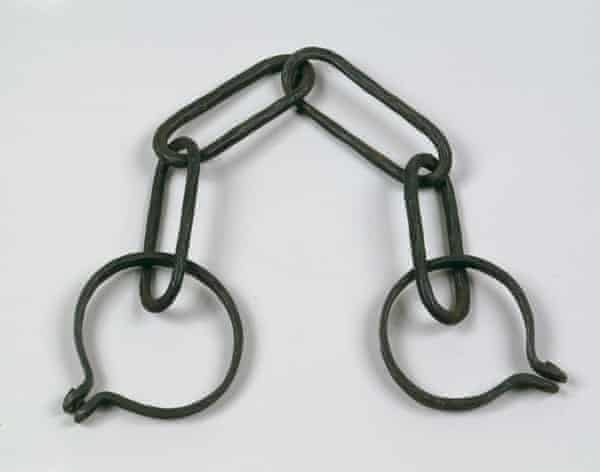

"This very endeavour to blot out forever the hopes of an enslaved people may be one necessary link in the chain of events preparatory to the downfall and complete overthrow of the whole slave system," Douglass told the crowd.

Eleven years afterward, Douglass' prophecy that progress would come up was realized: the 14th amendment overturned the Scott decision by extending US citizenship and equality earlier the law to all those born and living in the The states, regardless of race. And 2 years later, in 1870, the 15th amendment prevented restricting voting rights based on "race, color or previous condition of servitude".

But in the decades that followed, the court continued to rule in favor of limiting legal rights and protections for African Americans, often delegating the responsibleness of engineering greater racial equality to the states, where blackness people fought the forces of Jim Crow, the social and legal system of segregation and racial discrimination.

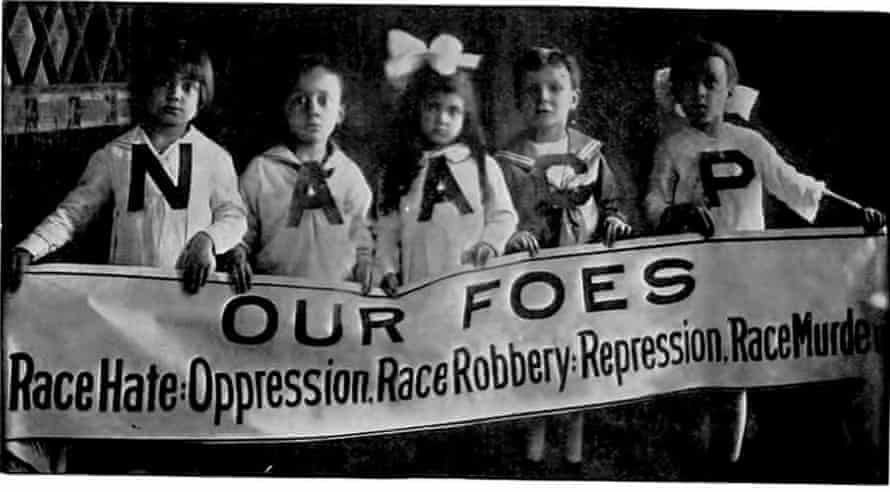

These years following the civil war and the struggle for black citizenship and equality that defined them are the field of study of Blackness Citizenship in the Historic period of Jim Crow, a new exhibit opening on at the New-York Historical Order and part of a new initiative at the museum exploring the history of freedom, equality, and civil rights in America. Black Citizenship – on view through 3 March – shines a light on the complexities of an era that spurred both advances and setbacks for black people in America, according to the curator.

"Our primary focus was on grappling with what the history of this period was, and that's a history that was mistold or undertold for many years," said Marci Reaven, the museum'south vice-president for history exhibitions. "We know that the ceremonious war was an extraordinary struggle, but what followed was also an extraordinary struggle in its own fashion: between equality and inequality, between democracy and repression, inclusion and exclusion."

Through an extensive written history and original documents and artifacts, the exhibit traces the roots of reconstruction to the rise of Jim Crow, highlighting the myriad black-led resistance movements and efforts to inhabit a fuller formulation of citizenship – a quest that began in hostage after the 13th amendment abolished slavery in 1865 and left open the question of African Americans' legal status, Reaven said.

"Although freedom was gained [through the 13th amendment], information technology was non clear what black people's condition was going to exist in the country – information technology was not immediately clear that they would exist citizens," she said.

Reconstruction – the postwar period of national rebuilding that stretched to 1877 – saw African Americans begin to seize some of the tenets of citizenship that they had previously been barred from: they built their own churches and schools, and black men voted and ran for function. Merely these advancements also fueled white resentment, leading whites in power to effort to curtail African Americans' agency through Jim Crow and attempt to reframe the history of the ceremonious war and Reconstruction past adopting the "lost cause" ideology, which held that slavery was benign and the pursuit of the Confederacy was honorable.

But the exhibit also shows how notable black activists resisted Jim Crow: journalist Ida B Wells published her investigation into lynchings in her 1892 book, Southern Horrors, and Spider web Du Bois founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People with a group of interracial men and women in 1909.

And black women fabricated particular efforts to create systems to protect and lift each other up in daily life, co-ordinate to the museum's project historian who studied the women featured in the exhibition.

"In that location was a real network and community of women looking to grade a safety cyberspace effectually their nigh vulnerable counterparts," said Dominique Jean-Louis.

Suffragist Mary Church Terrell founded the National Association of Colored Women, which developed a national network of local black women's clubs, in 1896; the post-obit twelvemonth, activist Victoria Earle Matthews founded the White Rose Mission settlement dwelling house for migrant black women in Manhattan; and Madam CJ Walker built a cosmetics empire and created a school in her Harlem brownstone where she trained black women to open their owns salons.

Reaven said that the history in the showroom shows that blackness men and women fought for citizenship in ways large and pocket-sized, by continually resisting the forces that sought to ensure their social and political oppression.

"One of the things that shone out to us in the inquiry is how profound the efforts were amidst blackness people to breathe real pregnant into their freedom, and then to go along to struggle for that even nether increasingly adverse circumstances," she said.

Hereafter exhibits as role of the museum's new initiative exploring the history of freedom, equality, and civil rights – funded in part by New York city council – will highlight the work of black women artists Augusta Fell and Betye Saar, and an exhibit next summertime volition commemorate the 50th ceremony of the Stonewall insurgence.

Reaven added that Blackness Citizenship and the museum'south hereafter exhibits focusing on civil rights are meant to remind visitors that pursuits for freedom and fairness are ongoing, and demand protection.

"The pursuit of democracy and equality require vigilance and stewardship – they're non atmospheric condition that are set and finished and finally achieved," she said.

-

Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow will open at the New York Historical Society on 7 September

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/sep/05/black-citizenship-age-jim-crow-new-york-historical-society-exhibition

0 Response to "Discuss the Quest for Racial Equality and Its Proponents in the Arts"

Post a Comment